More Than Nostalgia: The Power of Nollywood

A guest piece by Janelle Erskine, Black Women's Project Leeds, ahead of our collaborative screening of Living in Bondage

Janelle Erskine

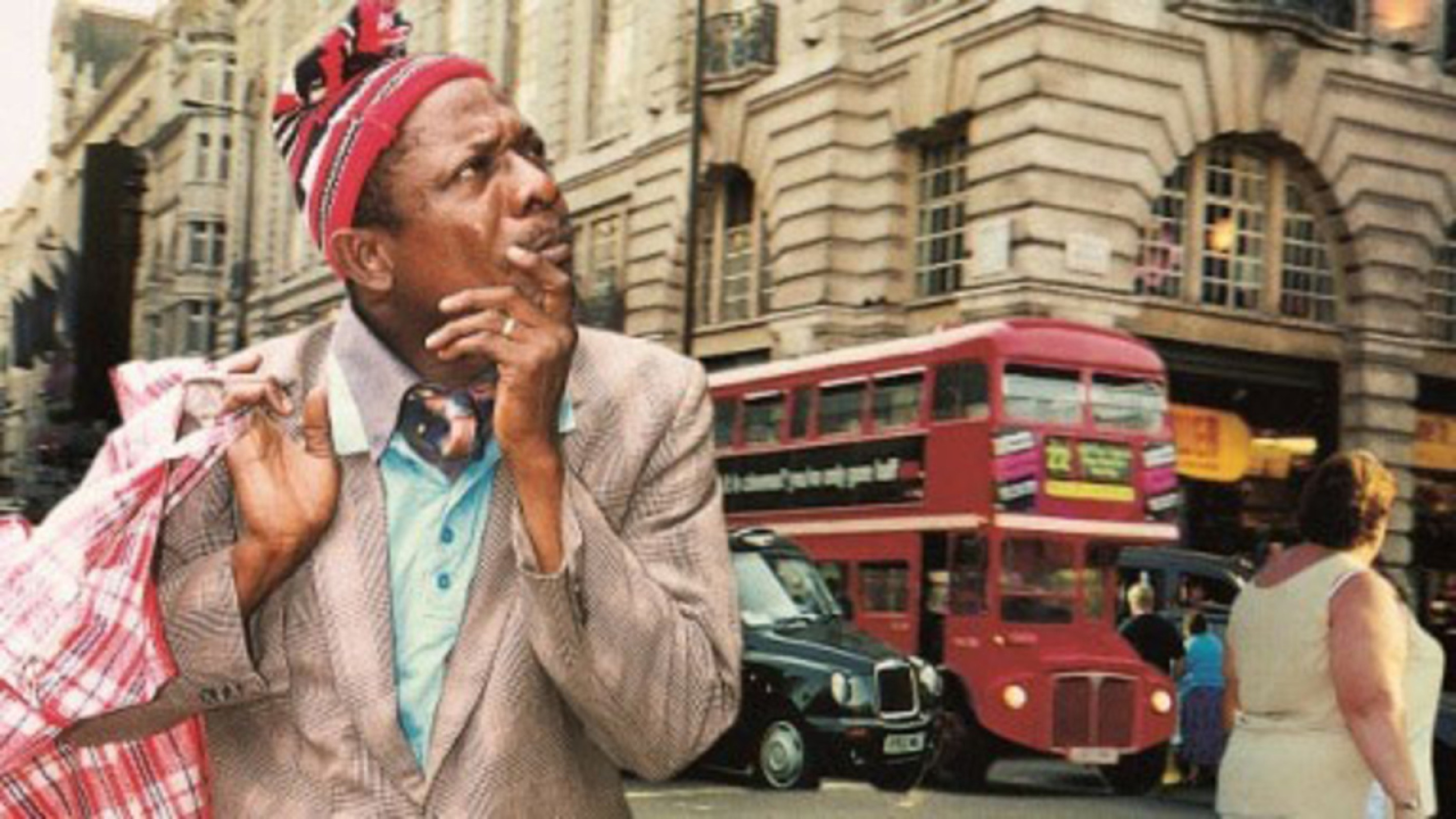

My earliest memories of Nollywood are tied to the soft pull of my mother’s fingers as she braided my hair on Saturday mornings. I’d sit between her knees, the smell of Blue Magic hair grease thick in the air, as the television flickered with the familiar opening credits of a Nollywood film. Osuofia in London might be playing, its humour bouncing through the room as my mother chuckled at the clash between Nigerian tradition and British absurdity. Or sometimes Blood Sisters, its intense drama pulling us both into a world where friendship, jealousy, and survival intertwined. Between the rhythmic parting of my hair and the stories onscreen, I began to understand something sacred about being a Black girl: the way beauty, pain, and resilience could coexist.

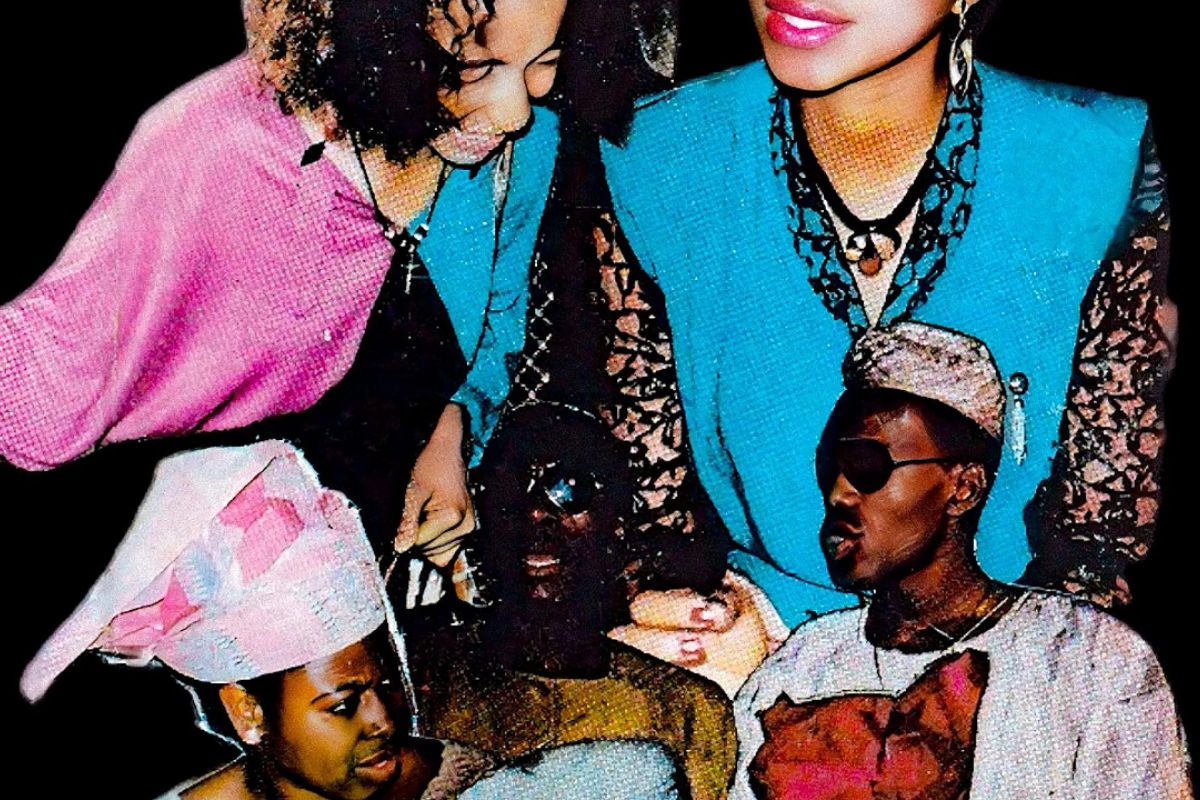

Those moments were my initiation into a culture I was still learning to claim. Growing up in the diaspora as the child of Nigerian immigrants, I often felt suspended between worlds, too African for school, too Western for home. But Nollywood became my cultural compass. Watching Living in Bondage taught me about greed, spirituality, and moral consequence in a way no Sunday school could. In The Wedding Party, I saw modern Nigerian glamour, laughter, chaos, and romance, all steeped in cultural specificity. These stories made me feel seen. The women on screen, Genevieve Nnaji in Ije, Omotola Jalade Ekeinde in Mortal Inheritance, Mercy Johnson in Dumebi the Dirty Girl, were complex and unapologetically African. They showed me that Black womanhood was expansive, not confined to one narrative or tone.

Nollywood’s cultural significance lies in its audacity. It was born from necessity in the 1990s, when filmmakers used home video cameras and bootleg distribution networks to tell stories the world wasn’t listening to. In doing so, they built one of the largest film industries on the planet, an industry that mirrors the diversity and contradictions of African life. For those of us in the diaspora, these films became a visual archive of memory and belonging. They grounded us when our surroundings didn’t.

What makes Nollywood extraordinary is how it uses storytelling as both reflection and resistance. Films like Lionheart, directed by Genevieve Nnaji, celebrate female leadership and modern ambition; October 1 interrogates colonial trauma; Isoken explores the pressure of marriage and identity in contemporary Lagos. These films speak directly to the social issues Africans face, gender inequality, corruption, and generational divides, while still managing to entertain. They also reimagine Black womanhood and girlhood with tenderness and complexity, reminding us that our stories deserve nuance and joy.

Even now, when I sit beside my mother on the couch, a Nollywood film flickering before us, the years between us seem to disappear. We still talk back to the screen, laugh at the melodrama, and predict which character will meet their fate first. In those moments, I see how Nollywood continues to braid our lives together, my mother’s memories of home intertwined with my diasporic longing to understand it. Watching these films is no longer just a nostalgic ritual; it’s a way of honouring where we come from and recognising that Nollywood, like us, has grown, bold, global, and deeply rooted in the art of storytelling that began right in our living room.

Janelle Erskine is the Secretary of Black Women's Project Leeds, who will be joining us to introduce our screening of Living in Bondage on Sat 22 Nov. You can book tickets here.