-wide.jpg)

Our history

We're always eager to discover more about our history so we will continue to add to this page whenever we learn interesting new facts. If you have any stories or pictures of the Picture House we'd love to hear from you! Please get in touch by emailing info@hpph.co.uk if you have anything to share.

The story of the Hyde Park Picture House began as far back as 1899 when Harry Child purchased the little corner we now call home.

Child’s family were well-known in the Leeds pub and hotel sector; the Mitre Hotel, Central Station Hotel and the Packhorse were all in the family. Child announced his plans to build ‘The Paragon’ and applied for a provisional alcohol licence which raised suspicions that this was going to be a pub rather than Child’s claimed ‘palatial hotel’. Locals vehemently opposed his plans and Child’s many licence applications were refused by Leeds Corporation Licensing.

In 1907, Child settled for the next best thing – a private club – as registered clubs were allowed to sell alcohol to members. He recruited Thomas Winn & Sons, who had also worked on the Mitre Hotel and the Adelphi, to build the Brudenell Road Social and Recreation Club which opened in 1908.

Harry's father, Henry Child, and Thomas Winn previously worked together in 1894 on a project to greet King George V in his visit to Leeds – they sculpted an arch made of 1500 loaves of bread!

Perhaps influenced by a new appetite for cinema, with the Lyceum and the Headingley Picture House (now Cottage Road) popping up in the area between 1912-1913, Harry Child decided to transform his club into a cinema.

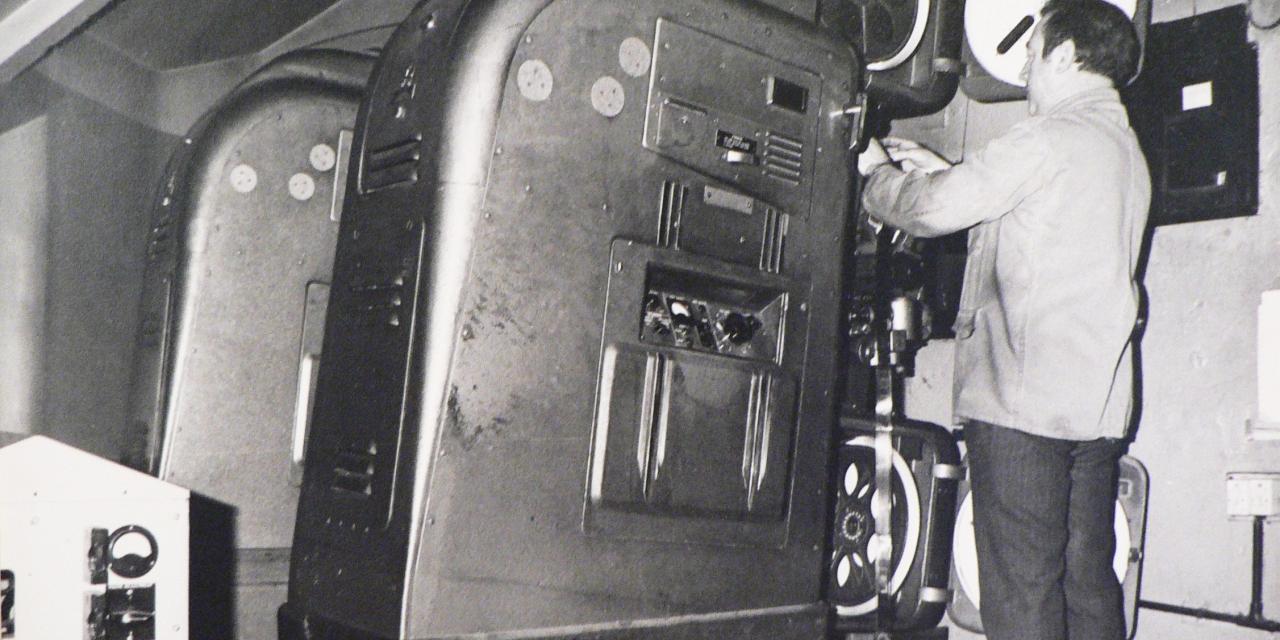

Prior to purpose-built picture houses, projections were free-standing in the middle of a hall, sometimes in ice rinks, warehouses or theatres. The use of powerful lamps, combined with highly flammable celluloid nitrate-based film caused lots of serious fires. The 1909 Cinematographic Act, which stipulated fire precautions such as a fire-resistant projection booth, marked the advent of picture houses.

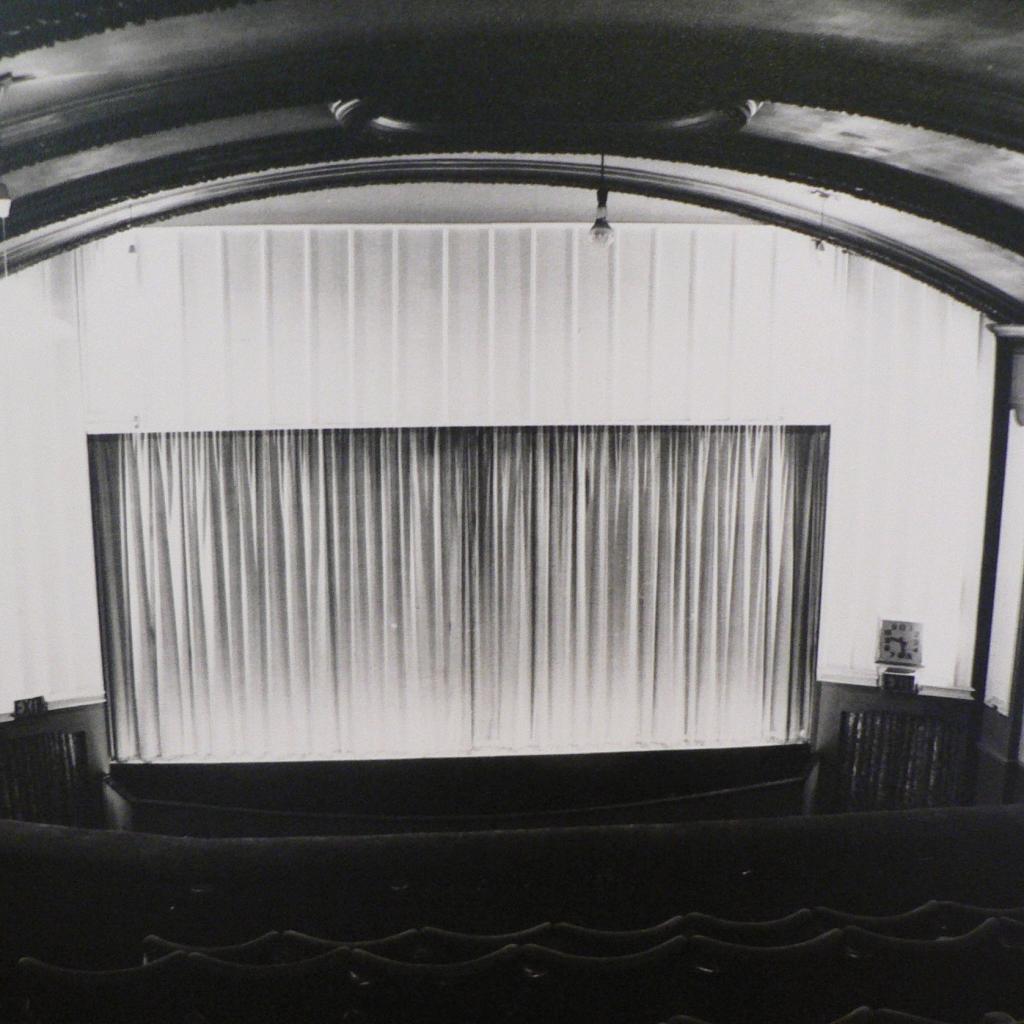

Child closed his club in December 1913 and the Brudenell Social Club we know today opened that year in its current location further down Queen’s Road. Child employed Thomas Winn again, this time to create a grand picture house which meant demolishing everything but the basement. Winn designed distinctive features we still cherish, such as the characterful façade with its iconic terracotta lettering; the white Burmantofts Pottery faience and Roman Ionic columns which contrast the red brick; and familiar flourishes including the decorative Dutch gable at the building’s pinnacle. Between the columns, Winn designed the external angled ticket kiosk. In the foyer, the grand staircase would have been coloured as it is today by light shining through the stained-glass window. Winn’s raked auditorium seated more people than today: 520 in the stalls and 150 in the balcony.

Although we pack less seats into the main auditorium today, lots of the original features still exist and are looked after by conservation specialists. We still have our original gas lights, making us the only gas-lit cinema in the country (perhaps even the world)! These were initially installed as modesty lighting to discourage the kind of indecency that penny gaffs (which came before picture houses) were associated with.

HPPH opened its doors on Monday 2nd November 1914. The opening programme largely consisted of patriotic silent, black and white films to boost morale during the war, and newsreels to keep people informed.

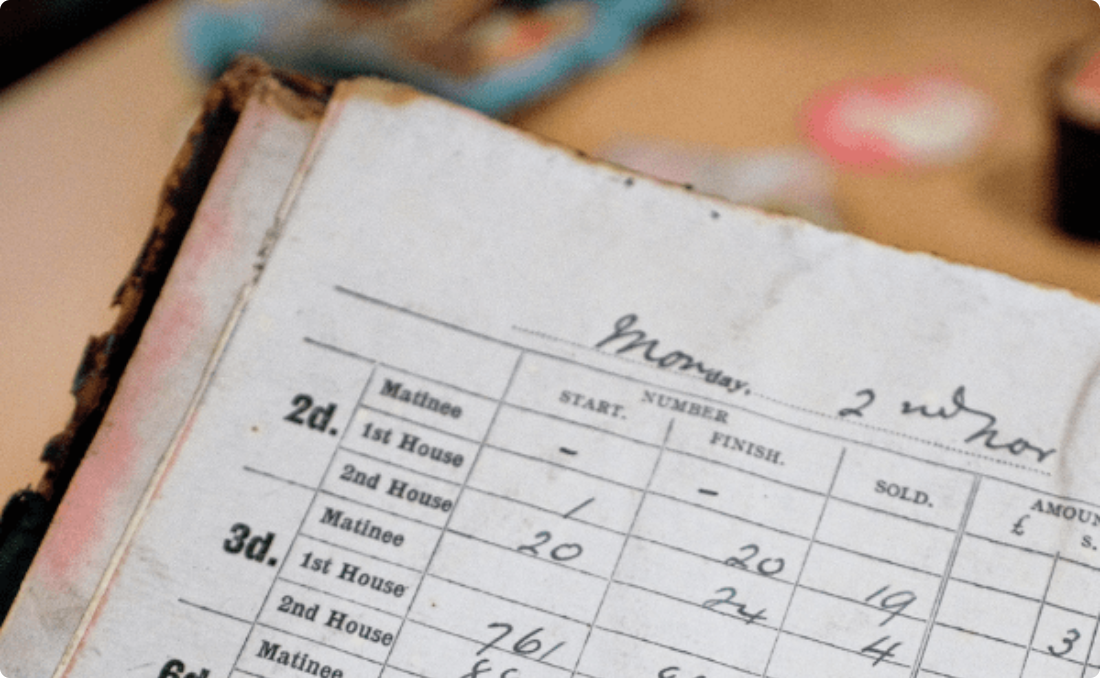

Daily logbooks exist from its opening until 1958, documenting screenings, weather, audience numbers, takings and other notes, including comments on public health with one entry stating ‘Soldiers and children barred – influenza epidemic’ in November 1918. From the logbooks, we know that there was a good turnout in the first week and almost a full house on the first Saturday. Audience numbers remained fairly high for most of the war, perhaps as it provided a welcome escape.

Two patriotic titles shown in the first week were Their Only Son and An Englishman’s Home. The Picture House was lauded by local press as the ‘cosiest in Leeds’ and praised for its ‘decorations […] on a most beautiful and lavish scale’. The manager, Joe Hardy, who lived next door to the cinema at 75 Brudenell Road, always greeted guests in evening dress. If he was late back to say farewell after sneaking out for a drink, the projection speed was slowed down. According to a young projectionist at the time, Harry Child took great pride in his cinema. When he visited once or twice a week, he would ask that the large crystal chandelier in the entrance hall be cleaned regularly and that the brass rods on the stairs and the glass in the projector ports be cleaned daily, even using his own handkerchief to clean on occasion.

Music was played in the Picture House by a trio: a pianist, violinist, and cellist. Ticket prices started at 2d, 3d, 6d and 1s before the 2d seats were reduced to 1½d in 1917. Patrons could buy chocolates, cigarettes and programmes. We’ve found evidence of these old items during the Picture House Project. We shared photos on social media with the hashtag #TreasureTrashTuesday, and you can see a rotating display of the discoveries in our new Café Bar.

In 1930, HPPH was adapted to show ‘talkies’, feature length films with sound.

During the Picture House Project, we discovered that behind our current proscenium arch there is evidence of a 1930’s Art Deco panel and behind this there is the original wall on which silent films would have been projected when the cinema first opened. This original wall is adorned with Baroque plasterwork: gilded cherubs, garlands and festoons. It is a rare surviving example of a screen from the silent film era. The newer Art Deco projection wall was built in front of the original one to make room for speakers to screen ‘talkies’.

The 1930s saw a growing interest in independent and foreign films, beyond the British and American ones the Picture House originally screened. In 1937, the Leeds Film Institute Society was founded. Their membership grew to around 400 and in 1938, they began to use the Picture House for public screenings of foreign and art films.

In March 1939, as WWII loomed, the HPPH was used for an armed forces recruitment talk, with figures like former suffragette Leonora Cohen urging volunteers to enlist before conscription became compulsory. On September 3rd, war was declared and all cinemas were forced to close. This was quickly retracted and the HPPH reopened its doors as soon as September 15th when the importance of cinemas for morale and distraction was realised.

Our lost cinemas of Leeds project, Hiding In Plain Sight, gives a sense of just how many cinemas were unable to survive in the years after the war with competition coming from multiplex cinemas, TV and VHS.

In January 1958, HPPH closed due to the crippling impact of rising interest in TV and larger city centre cinemas. Thankfully, the cinema reopened after two months.

Our building contains reminders of other cinemas which didn’t survive. The Art Deco clock in the main auditorium came from the Gaumont cinema which closed in 1961 and is now the O2 Academy, and our two Cinemeccanica 35mm projectors were from The Lounge in Headingley when it closed in 2005.

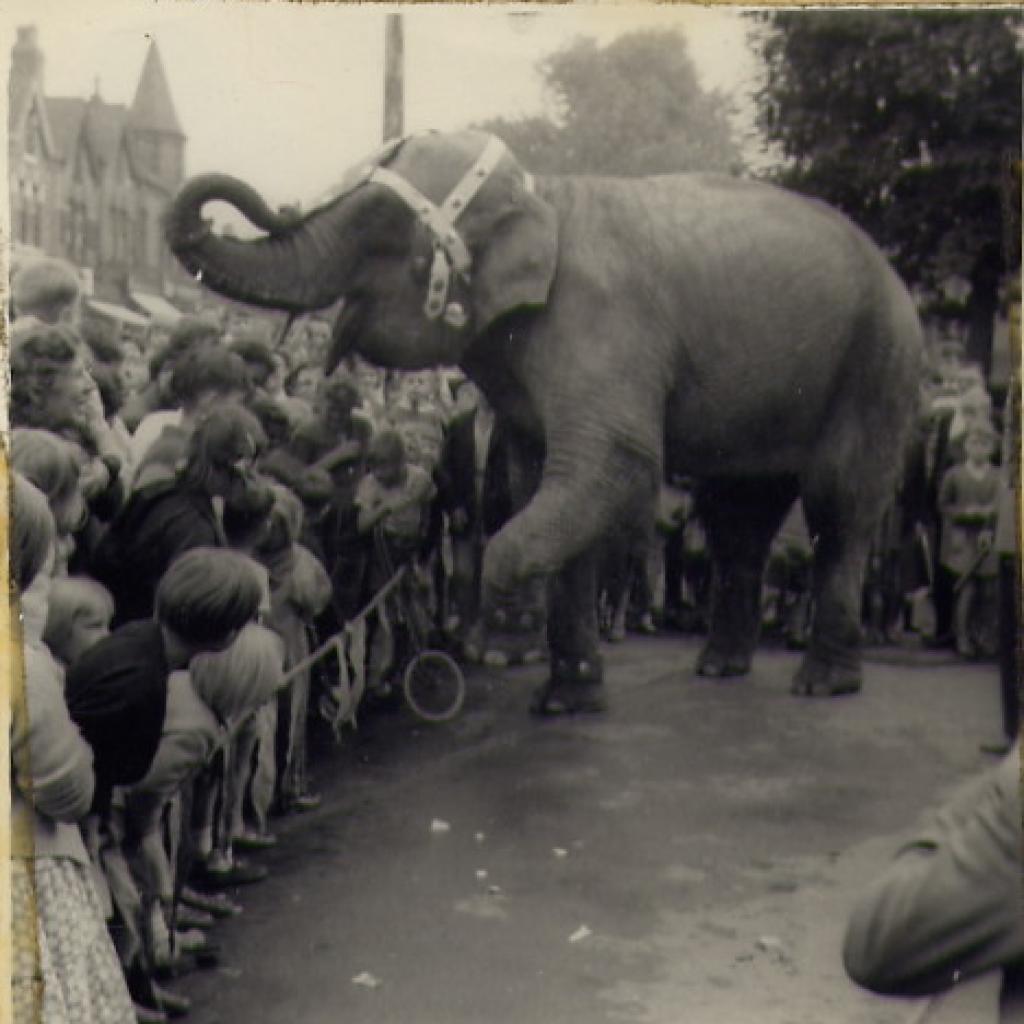

Management efforts to save the HPPH included a publicity stunt in 1959, where an elephant paraded outside the cinema to advertise The Big Hunt. Even more dramatically, the nephew of former manager Len Thompson re-mortgaged his home to save the cinema.

When HPPH was at risk of closure in the 1980s, passionate supporters of the cinema formed the charity Friends of Hyde Park Picture House in 1984.

The group are to thank for the listing of the building and the ornate external lamppost, and much fundraising over the years.

In 1987, the first Leeds International Film Festival took place at HPPH, a festival we still work with today.

In 1989, when at risk of closure, the Picture House was taken over by Leeds City Council to become part of what is now a separate charity, Leeds Heritage Theatres. We remain part of Leeds Heritage Theatres today with our sister venues, Leeds Grand Theatre and City Varieties Music Hall.

The cinema continues to evolve its programme and building while protecting its heritage features, to secure a long history for (hopefully) at least another century to come. From 2020-2023, the Picture House Project meant that the cinema was closed. During this time, specialist attention was given to conservation of heritage features; we expanded to create a new Café Bar, make our building more accessible and create a new screen in the basement. The Picture House Project was made possible largely thanks to funding from the National Lottery Heritage Fund, Leeds City Council and sponsorship from cinema patrons. During this redevelopment project, we discovered new artefacts from throughout the Picture House's history. You can read about our Treasure Trash Tuesday finds here.

This page was written with help from local historian Eveleigh Bradford and her research into the history of the Hyde Park Picture House for Headingley Development Trust.

| Cox, I. (1991) The Ornamental Ironwork of Walter MacFarlane and Co. Scottish Art Review, XVII, pp.3-7 |

| Gallagher, J. and Robinson, R. (1953) The Economic History Review New Series, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 1-15 DOI 10.2307/2591017 |

| (1899) Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 25 August |

| (1913) Leeds Mercury, 20 December |

| Hyde Park Picture House Management, (1914-1958) Financial records, film records and daily return books. WYL2359. West Yorkshire Archive Service. |

| (1914) Yorkshire Evening News, 11 November |

| Mannix, L.J. (1988) Memories of a Cinema Man. Associated Cinemas |

| (1930) The Bioscope, 20 August |

| (1938) Yorkshire Evening Post, 15 January |

| (1939) Yorkshire Evening Post, 18 March |

-(1)-smaller-wide.jpg)