A Game of Chance: Chess of the Wind (1976)

Looking forward to our screening of Chess of the Wind, with an overview of the history of lost films.

Robb Barham

It’s always an exciting moment when a film once thought gone forever or hidden away, is suddenly rediscovered or restored for posterity, adding immeasurably to the richness of our shared cinematic history.

Chess of the Wind (Shatranj-e Baad, 1976), screening as part of our reRun strand on Sunday 4th of February, is one such film.

Written and directed by Mohammad Reza Aslani, who is better known for his documentaries and experimental films, he made only two features; Chess of the Wind and Green Fire (2008).

It took Aslani six years to finance and make the film, but it was only screened once to a cinema audience before the Iranian revolution of 1979, when it was subsequently banned by the Islamic Republic and the original negatives considered lost. That is until 2014, when incredibly, they were rediscovered by the director's children in a junk shop.

Still prohibited even then, the film canisters were smuggled out of Iran and the film was finally restored by Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project. It was then screened at the 2020 Cannes Film Festival, after which this lost masterpiece could finally be screened to the public.

Chess of the Wind is a delicately poised and beautiful period thriller where the head of a rich, aristocratic family dies, leaving a paralyzed daughter as her sole heir. Relatives and servants of the dead matriarch then begin to vie for the inheritance, in a riveting, gothic tale of intrigue and deceit.

Within the main narrative, the film was also designed as a layered reflection of a rapidly changing Iran and of widespread societal corruption. With its foregrounding of strong female protagonists, it's deeply critical of the patriarchy, it was the first film in Iranian cinema to feature a lesbian scene, and it even finds time to break the fourth wall.

The film’s naturalistic lighting, subtle colouring and use of film tinting was influenced by European painting and filmmaking (Johannes Vermeer, Barry Lyndon (1975) and silent films respectively), and is structurally intriguing, for example, regularly featuring a Greek chorus of washer women who discuss the family’s and Iran’s history.

But there is more to be discovered…

A study by the US Library of Congress found that of the 11,000 silent films that were produced by the American movie industry between 1912 and 1929, only 14% (1,575) survive today in their original release condition, while another 11% survive in various imperfect formats. It’s impossible to know what beautiful cinema languishes in film archives and cupboards around the world.

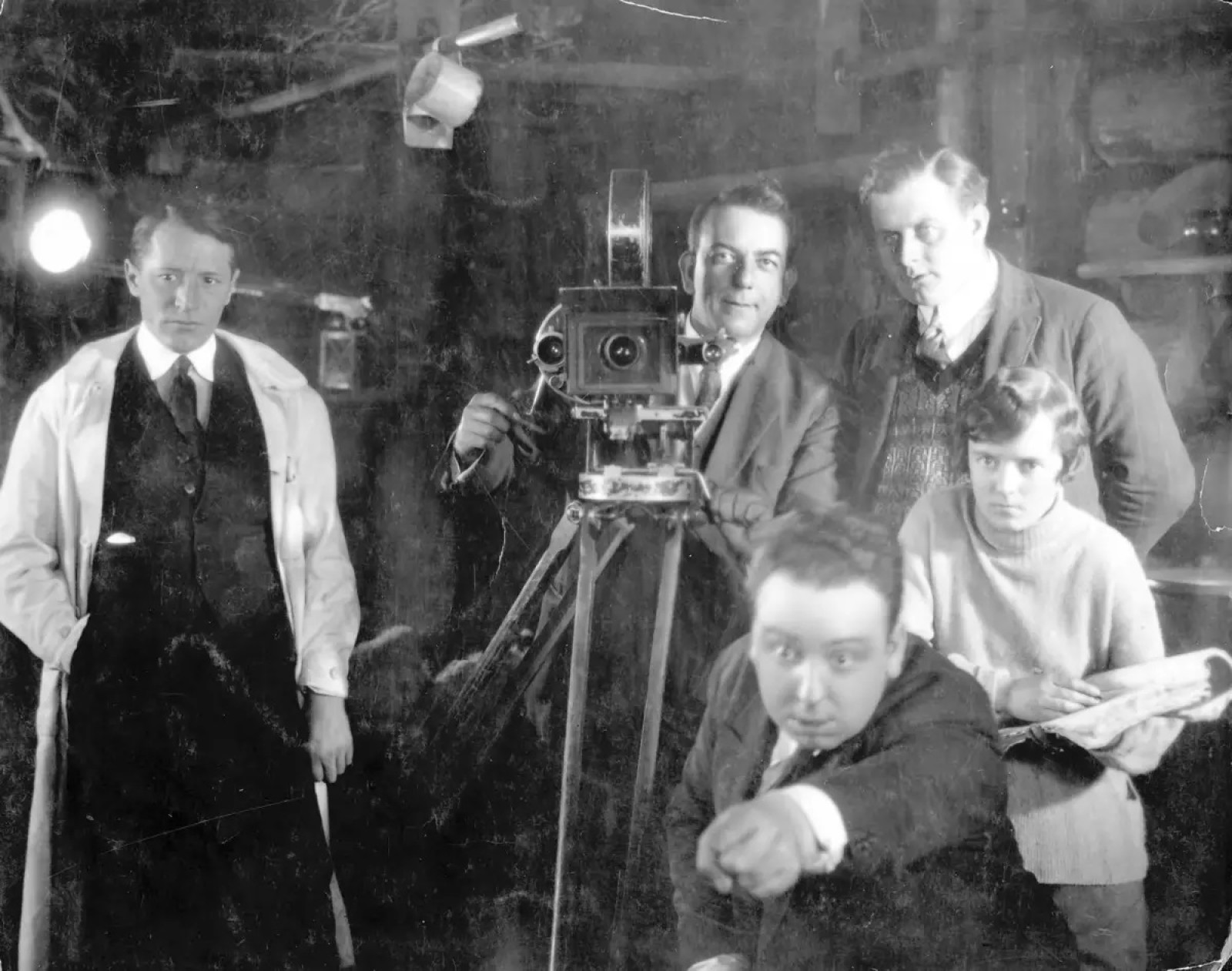

Reasons for a film’s loss vary widely. In the early 20th Century we just didn’t value films as having any longevity, or historical value as we do now, and most major studios would regularly burn films at the end of their run. Or sometimes, they would be dumped en masse in their own shallow graves.

A great example of this can be seen in the 2016 documentary Dawson City: Frozen Time, in which filmmaker Bill Morrison describes the incredible story of the rediscovery of over 500 nitrate film prints dating from the early 1900s, preserved in the Yukon permafrost for over 70 years.

That early films were created quickly and cheaply and because old nitrate film was extremely flammable, also led to films being stored in unsatisfactory conditions, resulting in their disintegration and in some cases incineration. Over the years, many studios suffered major vault, studio and film processing plant fires, which destroyed thousands upon thousands of film prints.

Amongst the most infamous missing films commonly mourned by historians and fanatics are The Mountain Eagle (1926), the second film directed by Alfred Hitchcock, and London After Midnight (1927), starring Lon Chaney and directed by Tod Browning, a silent mystery vampire film, now considered to be one of the most important and sought after of early western cinema.

However, many of the names of these lost films still survive, which remains an intriguing glimpse of what gems once existed, but have now passed into the void. Thankfully, filmmakers and cinephiles continue to wonder, seek out and creatively respond to these missing films.

In 2016 Canadian director Guy Maddin created Seances, which combined recreations of lost films, based only on their titles, with an algorithmic generator that allowed for multiple storytelling permutations. Seances creates a unique film every time, only to destroy them after their single viewing.

You can watch Seances online at the National Film Board of Canada.

Of course there are many other typical or more prosaic reasons why a film has been lost, barely screened, or indeed, not even released.

These range from theft, politics, colonialism, legal wrangling, creative differences, studio meddling, being banned, financial ‘irregularities’, filmmakers denouncing their own films, or simply refusing to screen them until a certain date of their choice. For example, Robert Rodriguez and John Malkovich’s short film 100 Years, which was shot in 2015, but has been placed in time-locked safes that won’t open for 100 years in 2115.

One of the more familiar of these lost (but luckily now found films), is Carl Theodor Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928). After being lost for years due to the master copy being destroyed by fire, a copy of Dreyer’s original cut, prior to government or church censorship, was found in a Norwegian mental institution in 1981. The film is now rightly considered one of the masterpieces of early cinema.

Then there’s the near mythical and controversial Jerry Lewis Holocaust film The Day the Clown Cried. Completed in 1972, his passion project was shelved by Lewis due to arguments about its finances, production and apparently being embarrassed by his own film (despite later changing his mind).

Reportedly Lewis has screened the film in private to friends, and in 2014 (before his death in 2017), he lodged a copy with the US Library of Congress, stipulating that it could only be screened 10 years later, in 2024, which apparently it will be in June of this year! Let's all hope it gets a wider release, and if it does, you can be sure Hyde Park Picture House will be at the front of the queue.

Whilst it’s a fact that most lost films will stay just that, some day, a few singularly rare moments of the unseen cinema of our world will resurface.

If you know where any are, do please let us know.