Book & film soulmates

We've had a think about our favourite book & film pairings. If you like one, we think you'll like the other.

Vee says if you like My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante, you'll like Beanpole (2019)

If you loved this novel about a homoerotic female friendship fuelling petty cruelties, you'll love this movie about a homoerotic female friendship fuelling worse cruelties. Both are stories of closer-than-close female friendships in the shadow of European war trauma, where the cruelty of codependency manifests as an emotionally cannibalistic desire to merge into one. Ferrante's beautiful prose and Balagov's beautiful winter colours form a sharp contrast to the ugliness of envying the person you love more than anything else. Beanpole is on MUBI now! Don't watch it if you want to feel happy.

- Vee, Venue Coordinator

Martha says if you like Hag-Seed by Margaret Atwood, you'll like Sing Sing (2024)

I read Margaret Atwood’s Hag-Seed around the same time I watched Sing Sing and they feel like a perfect pairing - I think if you like one you’ll also really like the other. Characters in Sing Sing aren’t haunted by grief in the same way Hag-Seed’s protagonist is, but they have their own ghosts - many of which are caused by a frustratingly unjust justice system. At the heart of both stories is an in-prison theatre programme which has a transformative impact on the prisoners. Arts programmes in prisons are something I feel passionate about and when I helped out at creative writing classes in HMP Norwich, I saw the positive escapism they brought to everyone involved - a chance to write themselves out of the many walls and stigmas they were confined in. The RTA workshops depicted in Sing Sing have proven benefits as less than 3% of RTA members return to prison, compared to 60% nationally. So, hopefully with more stories like this, particularly when they’re as well done as Hag-Seed and Sing Sing, people will realise the importance of funding these opportunities in prisons.

- Martha, Digital Marketing Coordinator

Alisha says if you like The Girls who Disappeared by Claire Douglas, you'll like Picnic at Hanging Rock (1976)

I think both pieces of art do really well encapsulating survivor's guilt and the sense of fear felt after losing friends in an incident. Both also showcase how easily narratives and perceptions can be changed after a traumatic event has taken place.

- Alisha, Volunteer

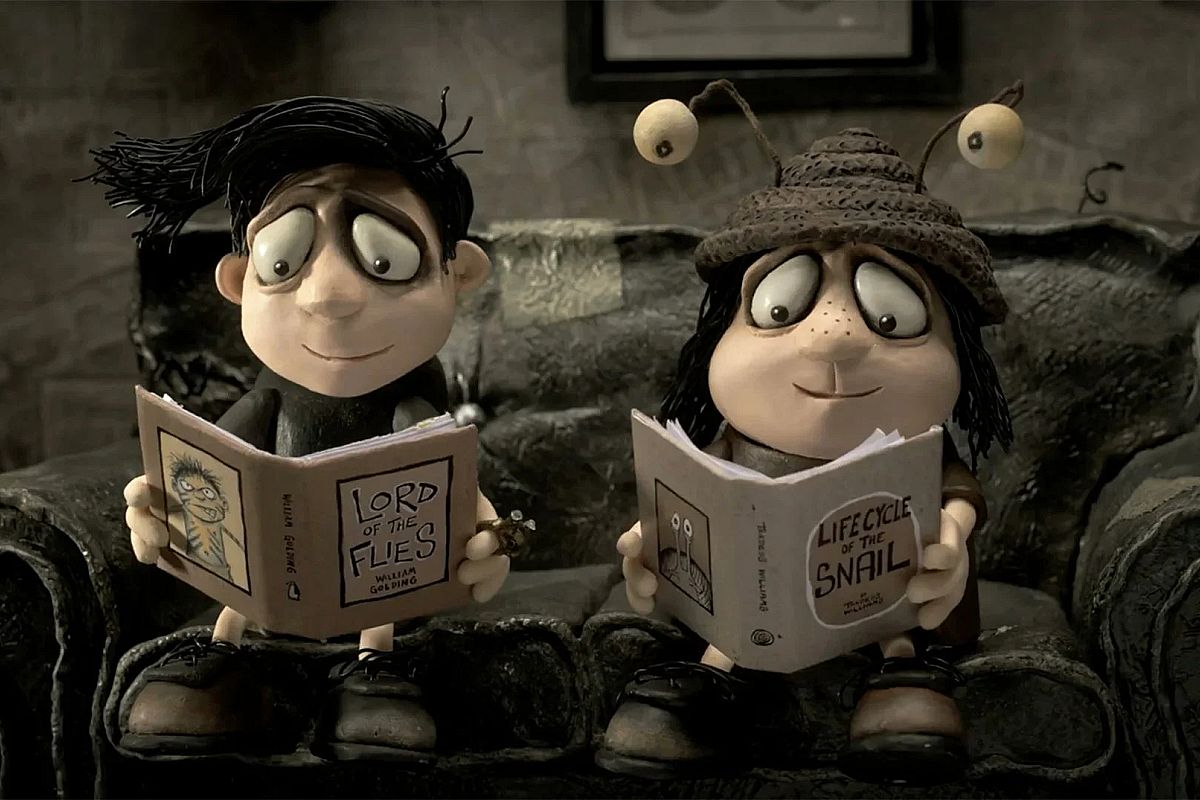

Lou says if you like The Book of Form and Emptiness by Ruth Ozeki, you'll like Memoir of a Snail (2024)

Both are coming-of-age tales dealing with grief and depression, and hoarding tendencies. They are also hopeful stories.

- Lou, Volunteer

Ian says if you like The Killer Inside Me by Jim Thompson, you'll like Strange Darling (2023)

Brutal and darkly comedic story of a deputy sheriff who is also a depraved sociopath in a small Texas town. Stanley Kubrick was so impressed with the book he sought him to help write the scripts for The Killing, Paths of Glory and the unmade Lunatic at Large. Jim Thompson has been adapted to the screen often but even the best adaptations don't capture the psychological depth of his characters.

- Ian, Volunteer

Jordan says if you like Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through The Looking-glass, & What Alice Found There by Lewis Carroll, you'll like Angel’s Egg (1985)

Wildly different in tone, I’ll admit: Carroll’s novels remain some of the funniest things for me, while, if there’s any humour in Angel’s Egg, it’s a dark one with the audience as its target.

Nevertheless, as in Carroll’s work plot takes a backseat to exploring the potential of playing with the stuff of storytelling, the words themselves, writer and director Mamoru Oshii uses a setting and characters to link together a phantasmagoria of explorations of various elements of our visual world and how pictorial art can depict them: shadows, reflections, windows etc.

The cels’ ink and paint can’t replicate designer Yoshitaka Amano’s iconic lightness of touch, which is so defining about his own drawings and paintings. But, instead, they take on the quality of Victorian etchings (though maybe more Gustave Doré than John Tenniel, to me) and are so complex that they result in a “boiling” quality, more associated with stop-motion or fully painted replacement animation rather than the flat colours and solid lines of conventional ink and paint.

Giorgio de Chirico’s paintings, the Cittàgazze of Philip Pullman’s The Subtle Knife, and Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities are other reference points – but I can’t boast of actually having read the last of those yet.

- Jordan, Cinema Services Coordinator

Charlie says if you like The White Castle by Orhan Pamuk, you'll like The Wind Will Carry Us (1999)

There’s a reason - or several - that while reading Orhan Pamuk’s 1985 novel The White Castle my mind occasionally flitted an eyelash at one of my favourite filmmakers, Abbas Kiarostami. Pamuk is Turkish. Kiarostami was Iranian. It would alas be wrong of me to conflate them too much purely on this basis, these after all being two highly separate and distinct cultures, despite being geographical neighbours. Perhaps this is simply a near-inevitable consequence of being a Westerner with limited knowledge of either. And yet, there are clear homogenising factors in this pairing.

Pamuk’s historical novel, set in 17th century Istanbul, concerns an Italian scholar who is sold in the Turkish slave market to a polymath who looks just like him, and their ensuing personal relationship, aesthetic and scientific exploits, and liaising with the imperial elites. They seem to complete each other, like a jigsaw puzzle whose interlocking shapes are ever-changing, so that one can never be too sure what makes one or the other their own individual self.

Kiarostami played with this osmosis of the self in its surroundings on numerous an occasion across his career, in such works as Certified Copy and Through the Olive Trees, among others, but it’s The Wind Will Carry Us that I’d like to discuss in comparison to The White Castle. In this film, a documentary filmmaker and his crew make themselves at home in a remote village under a number of guises, when their real intentions are to await an old woman’s death in order to then observe the village’s rural funeral rituals. They end up getting more than they bargained for, however, when the woman in question refuses to die.

Pamuk is a Cultural Muslim, identifying greatly with the Islamic world while not actively worshipping a God. Kiarostami was more overtly spiritual, but not politically so. Consequently, spanning both bodies of work one can find highly nuanced explorations of Muslim life that simultaneously critique the restrictions imposed on the person by the government according to said religion. Both artists eventually resorted to self-imposed exile from their respective countries in response to growing political antipathy to their creations.

Kiarostami preferred to tell stories in the present, in contrast to Pamuk’s tales of yore, and yet one can hardly tell the passing of a day between the Technicolor innovations in Pamuk’s bustling old Istanbul and the time-forsaken towns and valleys of Kiarostami’s latter-day landscapes. Nevertheless, the same shared love of both art and technology abounds in the twain, in the poetry recited by the director-cum-engineer in Wind, as in the authorial tinkerings of our protagonistic monster, sharing a face between two bodies, in Castle.

That each work is so elliptical in its own right is perhaps why it’s ultimately proving so evasive to hit upon the precise reason why these two artists strike me as so like-minded. Each work will, if nothing else, impart to you as tangible a sense of time and place as can be achieved through a piece of creative media.

Kiarostami was a master, both of words and of images. Pamuk is likewise, though he does well enough with just the letters.

- Charlie, Volunteer

Han says if you like Dog Days by Ericka Waller, you'll like Róise & Frank (2022)

Both the book and the film show the incredible healing power of dogs. The dogs in both brought lightness, joy and comfort to characters who were going through a lot of issues, such as grief and gave them a purpose and helped them cope with life's struggles and challenges. You can watch the film on BBC iPlayer here.

- Han, Venue Coordinator

To celebrate World Book Day, we've got some family events with the excellent storyteller Olivia Corbin-Phillip. She'll be joining us for a live storytelling performance before The Snail and the Whale (Friday, 11:00), and Where the Wild Things Are (Sunday, 11:30). We asked Liv about her favourite film adaptations of children's books. See what she had to say here.